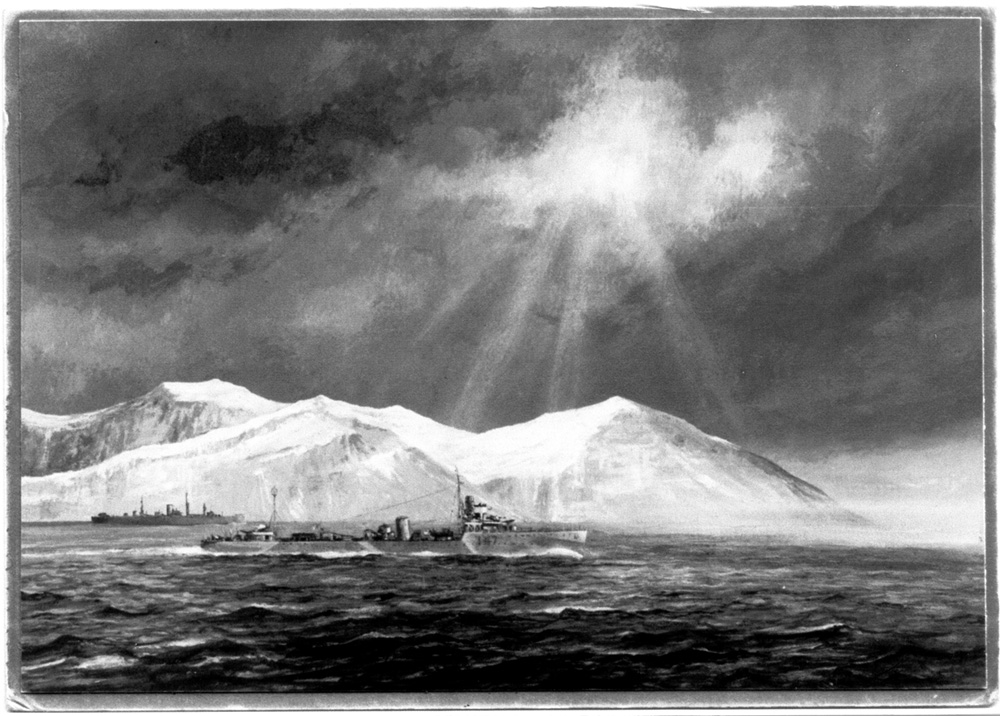

HMS WESTCOTT

HMS WESTCOTT Click on the links within this brief

outline for first hand accounts by the men who served on HMS Westcott and for a more detailed chronolgy

see www.naval-history.net

Commanding Officers

| Lt

Cdr C R Peploe (1918 – )* Lt Cdr A B D James (1930 – )* Cpt Lolly (1936 – )* Cdr Firth (1938 – ) * Cdr James Alexander Corrie-Hill, RN (Sep 1938 – Sep 1939 or Feb 1940) |

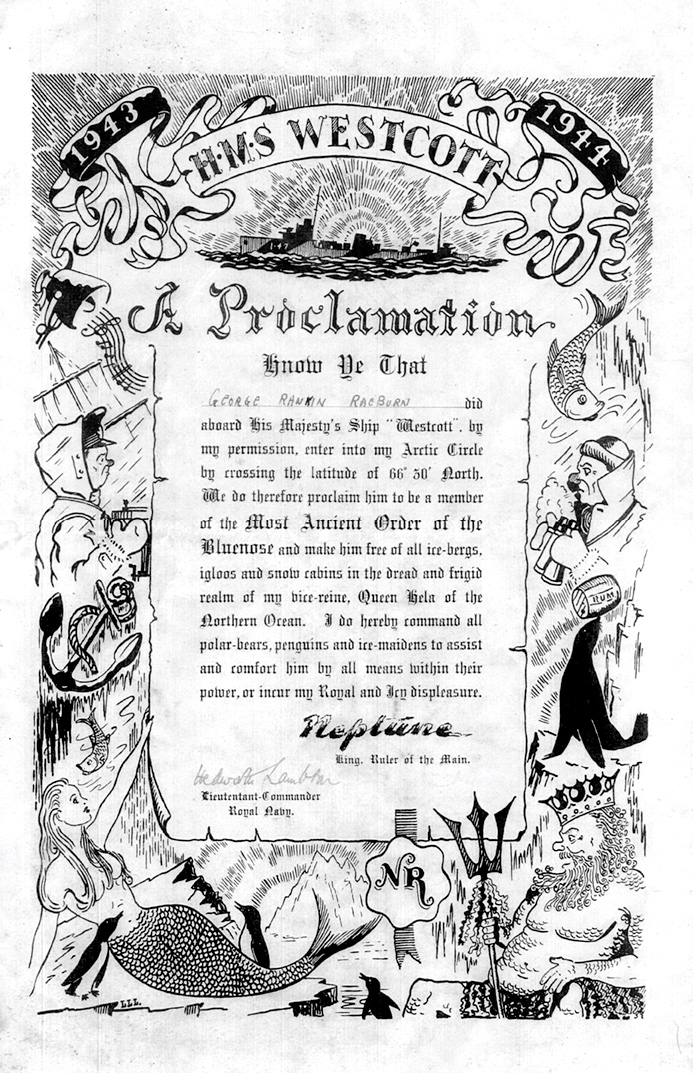

Lt Cdr William Francis Rodrick Segrave, RN (Sep

1939 or Feb 1940 – Feb 1941) Cdr. Ian Hamilton Bockett-Pugh, RN (Feb 1941 - Feb 1943) Lt Cdr Hedworth Lambton, RN (May 1943 – Jun 1944) Lt Cdr Edward Perry Reade, RN (Oct 1944 – Jun 1945) Lt J S de B. Smith (Jun 1945 - |

Officers

Further

names from the

Navy List will be added later.

| Lt.

C P d’A Aplin, RNR (Dec 1940 - Lt. F C V Brightman (Aug 1938 - Tempy. Lt. N D Britton RNVR (Oct 1943 - Gunner C W Chadwick (Apr 1939 - S.Lt. S B de Courcy-Iceland RN (1918 – 1919) Tempy. Surg. Lt. P U Creighton, MB, BCh, RNVR (Oct 1944 - Gunner (T) M Daniels (May 41- Lt.(E) R J H Duffay, MBE (Jul 1938 - Boatswain D H Easter (May 1940 - Lt. J N Elliott (Apr 1940 - Lt. S W M Farquharson-Roberts RN (Jun 1943 - Lt Arthur Lewis Gulvin RN (Feb - April 1940) Tempy. Lt. W J C Higgs, RNVR (Oct 1944 - Tempy. S.Lt. N J Hill, RNVR (Jun 1945 Lt. G R D Holland (May 1941 - Mid. L T H Johnson RNR (Aug 39 - Lt David Charles Kinloch RN (July 1930 - Jan 1932) Tempy. Gunner F B Leathers (Apr 1943 - Tempy. Surg. Lt. J D Loughborough, MRCS, LRCP, RNVR (Jun 1943 - Tempy. Surg. Lt. J D Manning, MRCS, LRCP, RNVR (Jul 1941- |

Tempy. Lt. A R A Marshall, RNVR (Jun 1943 - Gunner (T) S T Newman (act) May 1945 - Tempy. Act. S.Lt. A G C M Nightingale, RNVR (May 1941 - Lt Denzil Richard Cranley Onslow RNR (Nov 1942) Lt. C A H Owen (Aug 1937 - Lt. A Parsons, RNVR (Oct 1944 - Tempy. Act. S.Lt. W B Potts, RNVR (Apr 1944 Tempy Lt.(E) G R Raeburn, RNR (Jan 1944 - Tempy. S.Lt. W A Reeve, RCNVR (Dec 1943 Tempy. Lt. T S Riches, RNVR (Jun 1943 - Gunner J F Sangwell (Apr 1937 - Tempy. Surg. Lt. R Scott, MB, BS, RNVR (Jun 1940 - July 1941) Lt. J S de B. Smith (Jan 1945 - Tempy. Wt. Eng. A F Stapleton (Dec 1940 - Gnr Walter James Taylor RN (Sept 1936 - Feb 1937) Lt. N J M Teacher (Feb 1939 - Lt. A G Vanrenen (Dec 1941 - Lt Cdr Arthur Oliver Watson RN (Sept 1934 - July 1935) Tempy. S.Lt. J C Whitehead, RNVR (May 1945 - Lt. (N) W Whitworth (Apr 1937 - |

HARD LYING

Conditions on V & W Class destroyers were so bad in rough weather that the men who served on them were paid hard-lying money. These stories by veterans who served on HMS Woolston were published in Hard Lying, the magazine of the V & W Destroyer Association and republished in 2005 by the Chairman of the Association, Clifford ("Stormy") Fairweather, in the book of the same name which is now out of print. They are reproduced here by kind permission of Clifford Fairweather and his publisher, Avalon Associates. Copyright remains with the authors and photographers who are credited where known.They are reproduced here by kind permission of Clifford Fairweather and his publisher, Avalon Associates. Copyright remains with the authors and photographers who are credited where known.

Stormy Fairweather tells his own story below and in a recorded interview made at the reunion of the V & W Destroyer Association at Warwick on the 20 April 2013.

A 'Bunting Tosser' in HMS Westcott tells his Story

It was early January 1944, after

initial training at 'Royal Arthur at Skegness and signals training at

'Scotia' at Ayr. I found myself on a draft from Chatham to HMS Westcott

who was at the time berthed at Greenock. I arrived at Glasgow railway

station after a long and tedious journey. There were three others on

the same draft. When we reported our arrival, we were told that

transport down to the docks would not be available for at least an

hour, so to lose ourselves, we did not need a second telling so we

adjourned to the nearest watering hole where I was introduce to my

first 'Black and tan'. The most I had drank until then was the

occasional 'Brown Ale'. After three pints of this nectar we were called

to our transport, one of the Naval trucks. By the time we arrived at

Greenock I was a little worse for wear. However, somehow, I still don't

know how, I managed to negotiate two gang planks and landed on the deck

of HMS Westcott. I was

directed to what was to be my mess, down a hatchway to the mess deck.

It was early January 1944, after

initial training at 'Royal Arthur at Skegness and signals training at

'Scotia' at Ayr. I found myself on a draft from Chatham to HMS Westcott

who was at the time berthed at Greenock. I arrived at Glasgow railway

station after a long and tedious journey. There were three others on

the same draft. When we reported our arrival, we were told that

transport down to the docks would not be available for at least an

hour, so to lose ourselves, we did not need a second telling so we

adjourned to the nearest watering hole where I was introduce to my

first 'Black and tan'. The most I had drank until then was the

occasional 'Brown Ale'. After three pints of this nectar we were called

to our transport, one of the Naval trucks. By the time we arrived at

Greenock I was a little worse for wear. However, somehow, I still don't

know how, I managed to negotiate two gang planks and landed on the deck

of HMS Westcott. I was

directed to what was to be my mess, down a hatchway to the mess deck.

Bill Forster recorded an interview with

Clifford ("Stormy") Fairweather at Warwick on the 20 April 2013

You can click on the link to listen to "Stormy" describe his wartime service on HMS

Westcott

be patient - it takes a couple of

minutes before the file opens and Clifford starts speaking

My

father died in 2009 and never said much about his war and my own

memories are fading now. I believe he was proud of his involvement and

joining HMS Westcott, his

first ship, at nineteen changed his life, and not always for the best.

His fondest memories were of his time on HMS Westcott because of the sense of

comradeship he felt but he went on to serve on HMS Helvig, a mine-layer (or floating

bomb as he called it).

My

father died in 2009 and never said much about his war and my own

memories are fading now. I believe he was proud of his involvement and

joining HMS Westcott, his

first ship, at nineteen changed his life, and not always for the best.

His fondest memories were of his time on HMS Westcott because of the sense of

comradeship he felt but he went on to serve on HMS Helvig, a mine-layer (or floating

bomb as he called it).

On that day I was a 21 year old Lieutenant, one of three bridge watch

keepers in HMS WESTCOTT, a WWI destroyer, escorting the homeward bound

convoy RA.55A, roughly south of Bear Island. I had the middle watch, so

Christmas started for me at 0001 on the bridge. Course west, wind south

west rising to gale force, plenty of icy spray. We spent much of the

time finding four fleet destroyers, lent for protection, but to pass

them the message that they were now required to join the eastbound

convoy JW55B which had recently passed us.

My next watch was the afternoon, so Christmas lunch had to be taken

alone in the wardroom at around 1130. Our course was now northwest

towards the pack ice, presumably to distance us from trouble -

intelligence reporting that the mighty battlecruiser SCHARNHORST was

stirring and might be sailing north. The wind was now gale force and on

our port beam, strong enough to roll us 45 to 50 degrees to starboard.

To stop everything flying about, the wardroom staff secured the settee

and the two arm chairs hard up against the starboard wall settee, thus

making a comfortable channel in which to sit with lunch on one's lap,

without fear of the meal taking flight. Despite the turmoil the steward

produced delightful roast beef and a wonderful roast potato - why

"wonderful"? Because we only had upper deck stowage for vegetables, so

after three days out from our Russian port anything not eaten would be

frost bitten and ditched. The wardroom cook [bless him!] kept enough

spuds below to give us all one for Christmas. Otherwise it would have

been rice balls - edible but not quite the same. Next came the usual

figgy duff, nice enough!

Soon it was time for my duffel coat, oilskin and neck towel - at all

costs keep the icy spray off your chest! - and now the very careful

opening of the starboard watertight door to the upper deck. This has

five steel clips, one above and below, three down the side, the middle

where a handle would normally be. This one you leave to last, and seize

the moment when returning from the big starboard roll to get out. You

now have a few seconds in which to close all five clips, get round

forward of your superstructure where you reach a long, high, taut

jackstay reaching to the break of the forecastle. From it hang strips

of rope called lizards, with hard eyes so they can travel along the

jackstay. You grab one and start walking along the iron deck - V&W

destroyers have no passage below. Once or twice progress will be

interrupted when the big roll lets seawater foam across the deck -

"shipping it green", as they say. This can dislodge your seaboots'

slippery grip, but as long as you keep hugging that lizard you will

soon get going again. At least you can see things; midday in midwinter

at those latitudes gives you a dim dawn slowly turning into a similar

dusk, with about 21 hours of darkness ahead. Arriving at the forecastle

you change grip with care to a metal rung ladder - gloves essential,

the icy rungs would take strips off your bare hands - and after three

such ladders you are back on your open bridge.

Christmas afternoon brought the news that the SCHARNHORST and escorting

destroyers were at sea, probably after the laden outward convoy JW.55B,

that three of our cruisers were joining its defence. One was BELFAST,

still alongside at London. The Home Fleet was steaming east at top

speed to join the fray. In RA.55A

we were fast leaving the scene but could follow the Boxing Day ensuing

battle by radio, since Admiral Frazer in the battleship DUKE OF YORk

decided to use plain language for signals for greater speed of action.

As the gallant SCHARNHORST finally went down fighting there was

rejoicing, but 70 years on one remembers that only 36 survivors were

picked up from 1,767 men. Men probably very similar to us, and often

with a common enemy, the sea.

Lt. Stuart W M Farquharson-Roberts RN

During the 1930s unemployment was a great problem, good jobs were

scarce. I was fortunate in having a job, but with strings attached.

Located 60 miles away from home in Plymouth, it offered little in the

way of prospects. A case of waiting for 'dead mans shoes'. Financially

it was hopeless, after paying for digs and the fare home at the

weekends, I was broke. Eventually with the consent of my parents I

resigned so as to return to Plymouth to seek work locally.

After several unsuccessful interviews my morale was at a low ebb. A

family friend suggested that I might consider joining the Navy as a

writer, it offered job security and, of course at the end there was a

pension to be had. In those days a job with a pension was looked upon

with envy.

From enquiries I learnt that entry into the Writers branch of the R.N.

was by open competition held twice yearly, with an intake of about

thirty. With my future uncertain, I decided to go ahead and try to join

up. Following my success at the 1935 examination, I was

granted my choice of Port Division - Devonport and joined HMS Drake in

November as a new entry. Training was a combination of square bashing

and technical instruction and was completed without incident. I was

rated Writer and assigned to HMS Drake as a supernumerary.

A few months later with my official number hardly dry I received a

draft chit to join HMS Medway on the China station with passage as far

as Singapore on the V&W class destroyer Westcott.

Initially it was an unsettling experience, particularly bearing in mind

the distance involved and the period away would be at least two and a

half years. Air mail had not yet started which meant a letter would

take about six weeks to reach Hong Kong. The formalities of

a foreign draft being completed the days began to slip by and it wasn't

long before that on a cold blustery November morning with my

kit-bag and hammock I reported on board HMS Westcott. My first

impression was unforgettable, a mixture of super heated steam, hot

metal and the sounds of auxiliary machinery. My adventure was about to

begin! Most of the forenoon was occupied in settling in,

stowing away my gear etc; The seaman's mess would be my

home for the duration of the voyage, located in the fore part of the

ship, by any standards it was spartan. In the centre of the mess was a

steam engine used to drive the capstan, when the contraption was in use

the whole mess was enveloped in steam. Time is running out.

Tomorrow we leave these shores bound for the Far East and it's many

mysteries. Time for last farewells. The ships company offered theirs

some days earlier, being Chatham Division they had very few connections

with the West country. Weather conditions throughout the

night deteriorated, by daybreak the wind had reached gale force and was

still rising. Many vessels were running for shelter. A grim prospect

for us. With final preparations complete, securing lines

were cast off, the ship severed her link with the Devon shore and into

headed into Plymouth Sound, passing the mile long breakwater with it's

familiar lighthouse before entering the English Channel only to

encounter more severe weather, in fact, a 'No Go' area for an elderly

destroyer of just 1100 tons. Suddenly it happened, the ship turned

about and headed back to Plymouth, eventually making secure to the duty

destroyer buoy off Drakes Island. There we remained throughout the day,

come late afternoon there was a 'buzz', shore leave? Needless to say it

never materialised, for me as a 'sprog' it was a disappointment,

especially living in the locality. There was still a great deal to

learn about the Navy, particularly the need to take 'buzzes' with a

pinch of salt.

This voyage could be described as my introduction to Blue Water, I was

quite unprepared for such an experience that lay ahead. Racing 14ft

dinghies in Plymouth Sound offered little by way of preparation for

such a lengthy ocean passage. At about 11pm there occurred much

activity, the ship was being made ready for sea despite the

weather which showed no sign of improvement. It seemed that the

Commanding Officer, a Lieutenant Commander R.N. was faced with a thorny

problem and the ball was squarely in his court. He could either wait

for an improvement in the weather which would entail falling behind

with his schedule as a result or set off now.

How could he possibly maintain a schedule under these conditions? He

decided to slip and proceed. Leaving the shelter of Plymouth the motion

of the ship became increasingly violent, it was evident that we were in

for a trying night with the sound of the wind and the terrible pounding

from the sea, it was unnerving to put it mildly. Then suddenly it

happened, I collapsed being seasick violently and repeatedly. I really

did not care whether we did a vertical take off or plunged straight to

the bottom. I was not the only one, but the other victims seemed to be

at a lesser degree than I, but they were destroyer men and used to this

sort of situation. I take my hat of to them, one and all.

Had I been left to my own devices I may well have been swept over the

side. It was the Coxswain who put things right, patching me up and

twenty four hours later I was up and almost ready to make myself

useful. Never again was I to suffer from sea sickness despite going on

to serve in a variety of ships from Aircraft carriers to

Frigates.

Almost a week later we came alongside at Gibraltar where our stay was

extended to repair the storm damage. This would be a lengthy itinerary

which would offer countless opportunities for exploration of the

'Rock'. My first impression was its size, relatively small

with an area of about two and a half miles on the south coast of Spain,

commanding the North side of the Atlantic entrance to the Mediterranean

Sea which makes it important strategically. The main town at the North

western corner appeared to consist of a main street occupied by a

number of bars, there seemed to be three types, some had an orchestra,

others were a type of 'Bistro' bar, a drink that was popular at the

time was 'Coffee Royal'. This visit offered the perfect beginning to a

foreign commission, the easy stages in transit into a working ship

broke one in gradually. At journey's end one felt less of being a fresh

arrival on a foreign station. With repairs complete it was time to

press on to Malta, our next port of call, it was an uneventful leg of

the journey although useful in providing opportunities to increase the

efficiency of the ship’s company.

Upon arrival at Malta we did not rate very highly in the pecking order,

instead of the convenience of going alongside it meant tying up to one

of the many buoys. When shore leave was granted it meant going ashore

in what can only be described as a cross between a gondola and a canoe

called Dhaiso? The capital city, Valetta had much on offer to interest

new arrivals, the other principal centre being Sliema. Familiar sights

and sounds recalled are the milk vendor with his flock of goats, his

cry "Aleep, eggs, bread", the "Egyptian Queen" and the "Lucky

Wheel".

Leaving Malta in our wake we are now bound for Port Said. Since

clearing Malta it has become warmer, the sun reflecting off the surface

of Mediterranean with the sparkle of a million diamonds. The rig of the

day was changed to tropical in keeping with this type of

weather.

From now on more time must be allowed for washing clothes during dog

watches. The routine is simple, get hold of a spare bucket and a bar of

'Pussers' soap and you are on your way. I soon became a dab hand at

it. The time I spent in a seaman's mess as a junior rating

was priceless. I was taught how to prepare a meal for the mess, take it

to the galley, and fetch it when it was cooked. To keep the living

space clean and tidy, and above all, to show consideration to others.

These lessons I have never forgot and they stood me in good stead

throughout my life. The stay at Port Said was a short one.

I could not fail to be impressed by the statue in memory of Ferdinand

de Lesseps, the builder of the 101 mile long Suez Canal which was

opened in 1869 linking the Mediterranean and the Red Seas through which

we were shortly to make our way. Also worthy of mention were the twin

columns of the 1914-1918 War Memorial. The following incident remains

undimmed in my minds eye, but as the years pass I can see the funny

side of it. The ship was secured close inshore, it was during the early

part of the forenoon. A party of official types came on board, it

turned out that they were local Port Health Officials who had come to

carry out a medical inspection of the ship's company. All junior

ratings were summoned to fall in on the quarter deck, step up to the

official, drop your shorts and allow the said official, with the aid of

a large and powerful torch, to carry out the inspection, all this in

full view of the interested locals on shore.

Entering the Red Sea, change was evident, Western influence gave way to

the Eastern, particularly among the craft at sea, mostly sailing

vessels. The weather varied from cloudy to bright sunshine with rough

seas, nothing that I could not cope with. It was now that my request to

take a turn at the wheel was granted. I was elated, it isn't everyone

that could say that they had taken the wheel of a Royal Naval

Destroyer, especially a young writer.

Passing through Hells Gates we crossed the Arabian Sea to arrive at our

next destination Karachi, where much in the way of hospitality was

received. One incident still unforgotten was the street entertainer

with his act "Snake fight Mongoose 4 anna's.”

Then it was on to Penang where Christmas was celebrated, the mess in

common with the others was decorated with bunting and the menu

supplemented. A present from the Captain, an unexpected one, two

bottles of beer for each one of us. A generous act, particularly as,

apart from the rum issue, the Royal Navy was dry at least as far as the

lower deck was concerned.

Arrival at Singapore and soon a parting of the ways. Westcott would

stay and take over from HMS Bruce which was shortly due to return to

the U.K. whilst I was to make ready for the final stage of my

voyage. In January 1937 construction of the new Royal Naval

Base together with a vast dry dock was going along on apace. In the

mean time local R.N. affairs were conducted from HMS Terror, a monitor

armed with two 15" calibre guns, nearby was a medium sized floating

dock. It was real Boy's Own stuff. It was to HMS Terror I made my way

and explained that I had not been paid since mid October. Whilst

interim payments were made to the Westcott’s ships company no such

arrangements had been made for personnel on passage. Had it not been

for a postal order from my Mother received en route I would have been

up the creek completely. I was made welcome in 'Terror',

given a substantial advance of pay and told to avail myself of their

Chinese laundry which transformed my No 6's. It was six days later that

I reached Hong Kong, disembarked from H.M.T Lancashire and joined HMS

Medway at last. The beginning of what was to be a happy commission of 2

years in a splendid ship during which time I would visit many places of

interest throughout the Far East.

Many of the old V&Ws were now being put into reserve, others had

been earmarked for alterations and modifications to convert them into

the "Wair" type of destroyer. During the summer of !935 HMS

Wishart which was still under the command of Commander Lord Louis

Mountbatten was in the Mediterranean and whilst paying a visit to

Cannes welcomed his friend HRH the Prince of Wales accompanied by Mrs

Wallis Simpson aboard.

After taking my leave which was due after three years abroad I went to Vernon to qualify S.T. after which I was drafted to Valorous

as Ldg Seaman S.T. We were soon sent to Malta to join up with the 19th

Destroyer Flotilla and remained there until April 1936 when I was

returned to depot until September. I was then drafted to Westcott

which was at Devonport and being altered to attend on submarines,

picking up their torpedoes after practice firing. Leaving Guzz

(Gosport) in November 1936 in company with Thracian

we sailed into a stinking force 9 gale and by the time we reached

Gibraltar we were in a fine old state as we had aboard a number of

spare crew taking passage to other ships, they had been violently sick

in the galley flat for most of the trip, and as the coal for the galley

was kept there, it was in a fine old state, so were the seamen who were

covered in coal as the galley flat was always flooded in rough

weather.

After a few days in Gib' cleaning up and drying out the messdecks etc;

we carried on our journey to Malta and the Far East. During the journey

we managed to play any team that we could find at hockey or football at

every port that we called at, so by the time we reached Hong Kong we

had very good teams at both and also quite a good water polo team. Back

to work which consisted of chasing after and picking up the 'tin fish'

that had been fired by the submarines.

While we were out there in 1937-38 we managed to get hit by a typhoon

whilst in Hong Kong harbour. At the time I was Coxswain of the picket

boat from the 'Medway' and had to take a party of sick people ashore,

quite a trip. Earlier in 1937 when the Japs invaded China, our

Ambassador, Huggeson Knotchbull was on holiday with his family on the

island of Petaiho. Westcott

was detailed as guard ship to the ambassador and eventually we had to

transport the family from the island to a Cruiser for the trip back to

Shanghai. After quite a few incidents of Jap bombing and clearing up

hundreds of Chinese from the cables each morning we eventually came to

the end of the commission and came home in April 1939.